“Crossfire” serves up a solid mystery and a more powerful message

- Craig Shapiro

- Mar 28, 2021

- 4 min read

Updated: Jun 24, 2022

BLU-RAY REVIEW / FRAME SHOTS

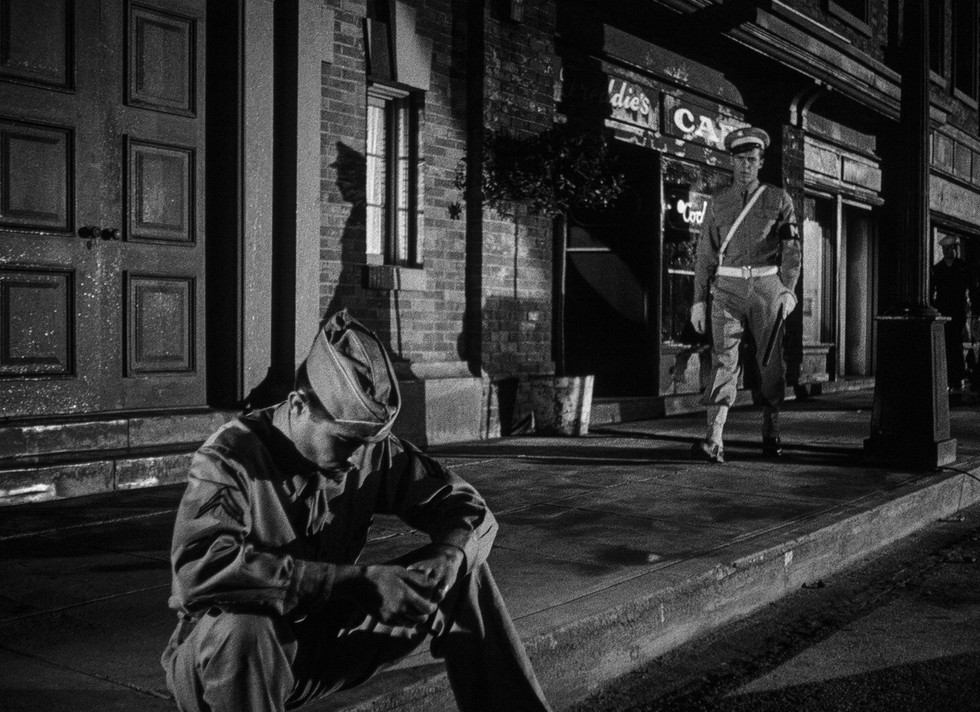

Police Capt. Finlay (Robert Young, right) tries to convince Army soldier Leroy (William Phipps) to help in the murder investigation of a Jewish man. Young went on to star in the popular TV series “Father Knows Best” and “Marcus Welby, M.D.”

(Click an image to scroll the larger versions)

“CROSSFIRE: WARNER ARCHIVE COLLECTION”

Blu-ray, 1947, unrated, themes, mild violence

Best extra: The 2005 feature, “Crossfire: Hate Is Like a Gun”

NEARLY 74 years after its release, “Crossfire” delivers a blow to the solar plexus. You can only imagine its impact when the curtain went up in August 1947.

When a Jewish man is beaten to death in his Washington, D.C., hotel room, the police focus their investigation on a group of soldiers seen with the victim in a bar that evening. Several are brought in for questioning, but the police can’t track down the prime suspect, whose wallet was found at the scene. His sergeant doesn’t believe he did it and starts his own investigation to find the killer. His identity is apparent early on, and so is his motive.

You don’t have to imagine the victim being Asian-American, Black or transgender.

Now, put the movie in context. It was made in 1947, two years after the end of the war, and Hollywood had never addressed anti-Semitism. That it resonated with audiences and the industry was clear when the Oscar nominations were announced: It received five, including best picture (it lost to the similarly themed “Gentleman’s Agreement”), director (Edward Dmytryk, “The Caine Mutiny”) and supporting actor (Robert Ryan, “The Wild Bunch,” “The Set-Up”) and actress (Gloria Grahame, “The Bad and the Beautiful”).

(1) Nominated for five Oscars, “Crossfire” was based on the 1945 novel “The Brick Foxhole” by Richard Brooks. It dealt with homophobia, a subject Hollywood wouldn’t touch in 1947. (2) Director Edward Dmytryk and cinematographer J. Roy Hunt filmed the opening sequence with deep film-noir shadows. (3) Finlay questions Miss Lewis (Marlo Dwyer), who discovered the body. She tells him that they had been having drinks in a bar with some soldiers who had been recently discharged. (4) Montgomery (Oscar-nominee Robert Ryan) shows up at the murder scene looking for a soldier named Mitchell and admits that he and another Army buddy had been in Samuels’ apartment with Mitchell. (5) Finlay later questions Mitchell’s best friend Keeley (Robert Mitchum). He believes his friend is innocent.

The other nod was for John Paxton’s (“On the Beach”) adaptation of Richard Brooks’ 1945 novel “The Brick Foxhole,” the same Richard Brooks whose film career included an Oscar for writing “Elmer Gantry” and nominations for directing and writing “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” and “In Cold Blood.” His subject, though, was homophobia, and that was off-limits in 1947 Hollywood. Ryan, who Dmytryk describes as “the most liberal man” on the set, was serving in the Marines with Brooks at the time and told him that if his novel was made into a movie, he wanted to play the bigoted Montgomery.

At any rate, Paxton’s narrative only appears to be straight out of the film noir playbook. The investigations overlap and the events leading up to and surrounding the murder are recounted from different perspectives. Viewers have to stay on their toes.

Its relevance isn’t the only reason to put “Crossfire” on your list. Veteran cinematographer J. Roy Hunt (“Room Service”) serves up all the film noir flourishes – deep shadows, sharp contrasts, stark angles – and then some. He distorts the image to imply a character’s drunkenness and uses different lenses as Montgomery’s true nature is revealed, beginning with a clean 50 mm lens and, at the end, an extreme 25 mm lens to show his monstrosity.

And the acting is solid, particularly Robert Young (TV’s “Father Knows Best” and “Marcus Welby, M.D.”) as the resolute police Capt. Finlay, Robert Mitchum (who starred in the noir classic “Out of the Past” the same year) as the cynical Sgt. Keeley, Grahame as the tough-talking Ginny, Ryan, George Cooper (“Blood on the Moon”) as the elusive suspect Mitchell and Broadway star Sam Levene (“Guys and Dolls”) as the victim Samuels.

(1&2) Keeley starts his own investigation to find Mitchell (George Cooper), who, having had too much to drink, is sitting on a curb when an MP comes across him. (3) In a flashback, Samuels (Sam Levene) consoles Mitchell at the bar. (4) Wandering into another bar, Mitchell starts a conversation with Ginny (Oscar nominee Gloria Grahame), a tough-talking taxi dancer. (5) Mary Mitchell (Jacqueline White) arrives in Washington, D.C., and is reunited with her estranged husband.

VIDEO/AUDIO

Add another feather to Warner Archive’s cap. “Crossfire” (1.37:1 aspect ratio), transferred in 1080p reportedly from a 4K scan of the original camera negative, doesn’t come close to showing its age. Blacks are deep, the grayscale is broad, detail is solid in both the close-ups and more distant shots and the cinematic grain is consistent. The focus goes soft a time or two, but that was more likely a decision made by Dmytryk and Hunt, and doesn’t detract from the proceedings in the least. Cue up the feature “Hate Is Like a Gun” and compare the new print with what passed muster in 2005.

The DTS-HD 2.0 Master Audio mix gets the most from the one-channel source, which is to say dialogue is clear and in-sync and the few gunshots pack a punch.

EXTRAS

There are only two, both from the 2005 DVD: “Crossfire: Hate Is Like a Gun” and a commentary with film historians Alain Silver and James Ursini, co-authors of “The Noir Style.” The latter splices in an archival interview with Dmytryk, who talks at length about his experience as one of The Hollywood Ten – the producers, directors and screenwriters who were called before the House Un-American Activities Committee. Fascinating. Looking back, he says they “misread the mood of the country.”

“Hate Is Like a Gun” doesn’t run long but it’s packed. Post-war disenchantment had fostered a run of films with a social conscience, but Dmytryk, in another interview, says he had to “out-think the censors” to get “Crossfire,” which he shot in 20 days (two less than allotted) for a measly $500,000, into theaters. Its subtlety and nuance are the foundation of its lasting power.

And as for the murder-mystery that drives it, Dmytryk says that was “the sugar wrapped around our medicine.”

– Craig Shapiro

(1) Montgomery finds Floyd (Steve Brodie), who was in Samuels’ apartment with him, hiding in Maryland and warns him that they better get their story straight. (2) As the police close in, Montgomery sweats it out.

Comments